The French Enigma

Basile Boli? No, I hadn’t heard of him either. But, in May 1993, Boli scored a unique goal in the history of French Football. His goal in a 1-0 victory for Marseille over Milan in the ’93 European Cup Final represents the only winning goal scored for a French club in the European Cup. Five years later, France lifted the World Cup in Paris; an affirmation of the quality of French football, and an exemplification of the detachment of the success of the France national team from its domestic league.

1993 European Cup Final: Marcel Desailly (right), Paolo Maldini (middle), Jean-Pierre Papin (left) amongst the stars.

So how is it that one of football’s great talent-producing nations has only one European Cup winning team? In most nations where such a disconnect exists there is an obvious explanation for domestic weakness. Brazil and Argentina, for example, suffer from lack of access to the Champions League and the resource-deficit associated with that. In a wider sense, The United States and Australia suffer from football not being their #1 sport, and thus the nations’ elite athletes are attracted to other sports. But the French trend has no obvious explanation, and is not a quirk of statistics. Yet watching Ligue 1 and its teams in Europe is ostensible proof that French football lacks something. This week, we dissect French football from the street footballer kids of Paris to the management structure of its top clubs, seeking to understand this curiosity.

Credit: MyGreatest11:

Marseille XI which won the 92/93 European Cup, the only European club competition victory for a French team.

French talent, coaching, mentality and marketing have all been assessed, and the French game is to be put to the test against two footballing nations it aspires to be superior than (Netherlands and Portugal), and four it aspires to equal (England, Italy, Spain, and Germany).

Credit: UEFA: Flashback to the 1993 European Cup Final

Talent: “Rare Pearls”:

The first thing every successful domestic league needs is a consistent stream of homegrown talent deep enough to service all its teams. Perhaps barring the Premier League, where economic success has allowed it to buy its way around a disappointing lack of top-level homegrown talent, the other three most successful leagues in the world are built upon academies. Italy, and particularly Spain and Germany, are leagues whose quality is reliant upon the success of its youth development. Netherlands and Portugal also follow this model, but their respective populations of 17m and 10m mean that they struggle to produce the depth required to service an elite league. France, on the other hand, boasts a 67m population, more than Italy (60m), and Spain (46m), so why does Ligue 1 lag behind its apparent equals?

FourFourTwo recently published an exhaustively researched list of the Top 100 Players as of 2019, and France (10), were represented more than Germany (9), Netherlands (4), and Portugal (3). Taking a moment to think about talented French players immediately brings to the fore a long list of names; Henry, Platini, Zidane, Kopa, Papin, Cantona, Fontaine et al. Those names are emulated in the modern game by Mbappe, Pogba, Griezmann, Kante, Varane, and the rest of the squad which emphatically thrashed Croatia in the 2018 World Cup Final. Such is the depth of top tier French talent that Benzema, Lacazette, Rabiot, Laporte, and Coman all failed to make the squad.

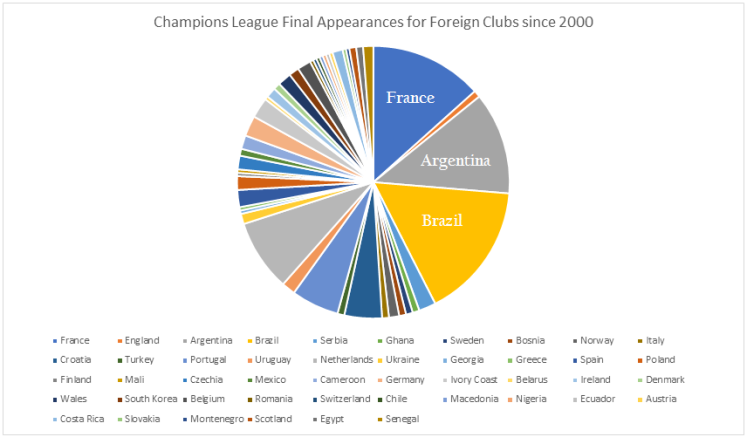

In fact, I compiled a list of all Champions League Final appearances for foreign clubs between 2000 and 2019, and France (33), were only bested by Brazil (40) in number of appearances by its players for foreign clubs. For context, that means that despite having their own European league, Frenchmen have appeared for foreign clubs in Champions League finals more than Argentinians. Some of the great European finals have been decided by French football academy graduates; Desailly in 1994, Zidane in 2002, Drogba in 2012. Top level talent is not an issue for France; the big issue is that only two of those players in FourFour Two’s Top 100 (Mbappé and Ben Yedder) play their professional football in France.

This begs the next question, is the elite level talent representing the national team and Europe’s top clubs supplemented by the volume of quality required to service an elite league? Yes, according to Yves Gergaud, a youth coach responsible for the nurturing of players such as Kingsley Coman (Bayern Munich), Presnel Kimpembé (Paris Saint Germain), and Ferland Mendy (Real Madrid). Gergaud gushes about the depth of talent in France, and says of the state of French street football “you find lots of players with high technical qualities, in terms of dribbling, tricks, and one-on-ones.” Again though, the exodus of top talent to Spain, Italy, Germany and England means that it is a bit arbitrary and false to infer a strong link between the street football of Paris and the strength of Ligue 1.

Therefore, perhaps it is on the streets of Dakar (Senegal) or Yamoussoukro (Ivory Coast) that we can make that link between street football and Ligue 1, as the void of French players in Ligue 1 is filled with talent from French-speaking Africa. This is a phenomenon so strong that newspaper Le Monde billed the 2002 World Cup showdown between France and Senegal as France vs France, and French historian Breulliac called it a contest between “the Senegalese of France” and “the French from abroad”. All members of Senegal’s XI were playing for French clubs, whilst only 1 of the France XI was playing in Ligue 1. For this reason, it is arguable that the strength of the French league mirrors the quality of French-speaking African national teams more than it does the French national team. Performances of Cameroon, Senegal, Ivory Coast, and Algeria have improved in the 21st century, and the inability to reach the latter stages of the World Cup has been attributable to a lack of tactical sophistication rather than a lack of talent. The obvious route of French-speaking Africans to Europe is through Ligue 1, where French clubs refer to “rare pearls” there to be purchased on the cheap from Africa. What the well-travelled route to France from French-speaking Africa does is further the affirmation that Ligue 1 should and does have the depth of talent to service an elite league.

Verdict: The French game has more top-tier talent and greater depth of talent than Belgium, Portugal, and the Netherlands. But it fails to retain that talent, and the quality of French football sidesteps the domestic game as its best players continue to leave with regularity. Whilst French-speaking Africa is on a positive trajectory, it cannot yet fill the void.

Coaching and Mentality: “Bunch of Imbeciles”:

So a top league needs the talent base, but it also needs quality coaching to harness that talent. In contrast to the enviable list of fabled on-field talents both past and present, elite French coaches do not immediately spring to mind. Wenger, Zidane, and Deschamps represent successes of the last 30 years, but even the latter two of that trio have not established solid credibility in terms of tactical excellence. For Zidane, Real Madrid always look on the verge of implosion; a trait borne-out in the 1-4 thrashing at home to a tactically superior Ajax in 2019. And like Zidane’s Madrid, Deschamps’ World Cup winning France side has never quite shaken the tag of a team that is less than the sum of its extraordinarily talented parts.

In contrast, instances of calamitous and disastrous French coaching are far easier recalled. France’s fabled 2010 World Cup implosion is characterised by coach Raymond Domenech, who was in charge as France went out in disgrace in the group stage. Amongst other outbursts Domenech described the French squad as a “bunch of imbeciles”, and singled out Nicolas Anelka as “an enigma who does nothing for others”. The lack of quality in French coaching is exemplified in analysis of foreign coaches operating in England, Germany, Italy, Spain, and France. There is currently a solitary French coach (Zidane) operating outside of France in Europe’s top 5 leagues, behind Spanish (3), German (4), and Portuguese (5). But beyond the statistics, it simply takes watching a Bundesliga, Serie A or La Liga game to find proof that the Spanish, Italian and German coaches are tactically superior to the French.

Credit: L’Equipe:

2010 World Cup Headline of an exchange between Anelka and Domenech:

“Go f*** yourself, dirty son of a b****”

The vacuum of elite French coaches is not solely due to limited coaching ability; it drives at a contentious and ugly facet of French football. Digging-down into the failings of Domenech’s France, there is a profound statement from the disgraced coach who said “I couldn’t bear to hear everyone giving their opinion on everything. I just wanted to be sick, to cry, to leave.” This encapsulates a tricky and interesting subject to broach, and that is the mentality and attitude of French footballers. There is compelling evidence that France produces far more players with difficult personalities and attitudes than most, and this also translates into a lack of desire to conform to the demands of coaches focused on tactical work.

The 2010 World Cup squad was full of players with a history of arrogant and disrespectful behaviour, with Franck Ribery and Nicolas Anelka being prime examples. Beyond that squad, Paul Pogba has proven himself almost unmanageable at Manchester United in recent seasons, Ousmane Dembele’s commitment has been questioned after missing training sessions at Barcelona, Antoine Griezmann made that film about his decision to leave Atlético, and Adrien Rabiot is exiled from the national team for refusal to be on standby for the 2018 World Cup. If this attitude is rife at the pinnacle of the French game, then it is natural to assume it is an issue which permeates into Ligue 1 and its academies. As an exemplification of this, Lyon’s decision to introduce a psychology department at their youth development centre was borne from necessity after too many talented youngsters drifted out of football due to behavioural difficulties.

This assumption about the French game is ratified by their receptivity (or lack of) to one of the great tactical minds in football history, Marcelo Bielsa. After failed spells at Marseille and Lille, the underlying sentiment from former players is that Bielsa was too difficult to play for. Former Marseille midfielder Romain Alessandrini said of Bielsa: “we did not take pleasure in training: only passes, tactical tricks, races and very little game. In the locker room, we were fed up. It worked for the first six months. We let go mentally or physically, I do not really know”. Bielsa is certainly demanding, intense, and obsessive, but there is no doubt he improves players. Thus, an opportunity for French players to grow, and for French coaches to learn in close proximity to a great coach was scuppered by an aversion to tactical learning.

Marcelo Bielsa, described by Pep Guardiola as “the best coach in the world” struggled to convince French players of his methods.

At best disinterest, at worst derision, this underestimation by players of the importance of elite coaching is replicated in the French media. Whilst Unai Emery divided opinion in England, there is no doubt that he represented one of Ligue 1’s highest calibre coaches during his time at PSG. Yet, the prevailing sentiment upon his departure was of a coach who neglected management of personalities in favour of an obsession with tactical minutiae. Again, French football dispensed with a fabulous coach who wanted to coach too much.

Verdict: The lack of quality in French coaching and the disrespectful mentality and attitude of French players has created a self-perpetuating cycle for the French league. Top coaches are deterred by the perceived failures of Emery, Bielsa and the like, and these failures are indebted in-part to the players lack of appetite to embrace a more tactically-focused coaching style. Meanwhile, French players disinterest in tactical growth causes clubs lose faith in coaches who prioritise tactics over ego management.

What Next? “La Ligue Des Talents”

In 2018, the French Football Federation re-branded Ligue 1 as La Ligue Des Talents (The League of Talents); a slogan aimed at promoting the youth of France and French-speaking Africa as an attractive selling-point for Ligue 1. The fact that this slogan only appeared after hours of research on French football suggests it has not permeated outside of France. Whilst Ligue 1 retains the 2nd highest domestic TV deal in Europe behind England (over £1bn), when international revenue is factored in Ligue 1 clubs receive less than half the average television income of clubs in Germany, Spain and Italy, and a quarter of the sums received by English clubs.

Ligue 1: “The League of Talents”

If you take England as an anomaly, the unwelcome fact for France is that re-branding and international interest must come second to improving the on-field spectacle. Germany are the prime example to follow, as a league with no obvious bedrock of overseas following (unlike Spain with Spanish-speaking Latin America). Yet over the last 5 years international viewing figures for the Bundesliga have increased in-line with the quality of football. This is not down to a sudden influx of money, it has been a gradual improvement as German coaching has prioritised a modern and attractive style through the likes of Nagelsmann. Accelerated by the profound influence of Guardiola during his time at Bayern, Germany exemplifies how receptivity to elite coaches can help transform the quality of a league.

For the moment, inclusion of France in discussions of Europe’s Top 5 Leagues sits uneasily. Perpetual failure in both the Champions League and Europa League is mirrored in Ligue 1, where the rising threat of Lyon, Marseille and Monaco to PSG has again subsided. Yet the untapped potential of French football remains enormous. If it is prepared to embrace a modern coaching style and nurture the mental development of its young players, then all the tools to sustain genuine Top 5 Leagues status. If Ligue 1 can do this, maybe Basile Boli will not be the only name associated with a European Cup win for a French club…

How French Football Works is part of a fortnightly Podcast and journalistic series called How Football Works. Find us on Apple Podcasts and all good Podcast apps.

If French football history interests you like it does me, I thoroughly recommend Migrations and Trade of African Football Players by Raffaele Poli.

The How French Football Works podcast is available from 24/05/2020 at Apple Podcasts and Spotify Podcasts, and goes includes greater depth on French-African Imports, as well as the Weekly Quiz, and more.

If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please submit them to @WorksFootball on Twitter, or to CJSHowFootballWorks@gmail.com. If you want to support this series, you can do so at Patreon.com/cjshowfootballworks.

Tell your friends!

Thanks for reading/listening, see you next time.

Chris x

Episode List:

-

- Episode 1: How Boca Juniors Works.

– Apple Podcasts

– Article - Episode 2: How Real Madrid Works: Total 80s Edition.

– Apple Podcasts

– Article - Episode 3: How The Galacticos Worked: Part 1.

– Apple Podcasts

– Article - Episode 4: How The Galacticos Worked: Part 2.

– Apple Podcasts

– Article

- Episode 1: How Boca Juniors Works.